Biblical Definition of Gratitude

Gratitude and thankfulness are one and the same. The virtue is one that God calls us to cultivate through life. The modern dictionary defines gratitude as, “the state or quality of being grateful or thankful; a warm and friendly feeling in response to a favor or favors received; thankfulness.” It was the Apostle Paul who wrote:

(Colossians 3:15) 1NIV New International Version Translations– “Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, since as members of one body you were called to peace. And be thankful.”

Gratitude is the expression of appreciation for what one has received. It is a recognition of value independent of monetary worth. Gratitude is spontaneous and generated from within us. It protects us from feelings of entitlement, envy, and resentment, which robs us of joy in life. Why be thankful?

(Romans 5:8) – “But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.”

God Himself sets the example for being thankful, even to mere humans! Hebrews 6:10 states, “God is not unjust; he will not forget your work and the love you have shown him as you have helped his people and continue to help them.” Yes, God considers it unrighteous, or unjust, to show a lack of gratitude. When we express “sincere gratitude,” whether for a gift, a kind word, or practical help, we make the giver feel valued and appreciated. Even strangers respond to people who thank them for doing a simple deed, such as holding a door open.

(Luke 6:38) – “Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.”

The Bible has much to say about gratitude and thankfulness. Giving thanks to God is of such basic importance that the Bible mentions the failure to do so as part of the basis for God’s judgment against mankind (Romans 1:21). We should also be thankful to God for the everyday things He provides to us. Gratitude also extends to the acts of kindness, gifts, and love others extend toward us. It is good to acknowledge the efforts of others to show our gratitude.

Foremost, we are to be grateful for God’s gift of life on earth and His gift of eternal salvation. Apart from Jesus Christ we only deserve eternity in hell (Romans 6:23; John 3:16–18). Salvation involves more than rescue. God has given us eternal spiritual blessings by uniting us with Jesus Christ through faith. If we are united with Christ, we have received forgiveness of sins and now are part of God’s eternal family (Ephesians 1:3–14).

Now for the hardest part of gratitude, being thankful for our trials in life.

(James 1:2–4) – “Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance. Let perseverance finish its work so that you may be mature and complete, not lacking anything.”

Why would anyone be thankful for such terrible things as trials, hardships in life? The answer is because even bad things work together for the ultimate good of those who love God (Romans 8:28). The goals of a Christian life are to live our life like Christ. God uses trials, temptations, and tribulations to grow us and mold us into the likeness of His Son. Trials to make us stronger and smarter. The foundation of gratitude is understanding that God is sovereign. His providence in working all things together for the good of those who love Him is why we are grateful.

(Philippians 2:13-16) – “for it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose. Do everything without grumbling or arguing, so that you may become blameless and pure, ‘children of God without fault in a warped and crooked generation.’ Then you will shine among them like stars in the sky as you hold firmly to the word of life. And then I will be able to boast on the day of Christ that I did not run or labor in vain.”

We have so many reasons to thank God, and yet it is a far too rare practice in society today. Complaining and grumbling come too easily. We are debtors to God and need His grace. The eternal life that we have received through faith in Jesus is worthy of gratitude (John 3:15).

Example of Biblical Gratitude

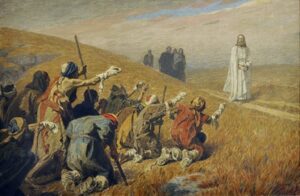

One of the best stories about gratitude comes from an encounter between 10 lepers and Jesus.

(Luke 17:11–19) – “Now on his way to Jerusalem, Jesus traveled along the border between Samaria and Galilee. As he was going into a village, ten men who had leprosy met him. They stood at a distance and called out in a loud voice, “Jesus, Master, have pity on us!” When he saw them, he said, “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went, they were cleansed. One of them, when he saw he was healed, came back, praising God in a loud voice. He threw himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him—and he was a Samaritan. Jesus asked, “Were not all ten cleansed? Where are the other nine? Has no one returned to give praise to God except this foreigner?” Then he said to him, “Rise and go; your faith has made you well.'”

The analogy formed here is that we are all born lepers. Everyone has a disfiguring and alienating disease called sin. Yet, Jesus took on the punishment due to our sins. He bore the bruises, pain, and death because we were not able to present ourselves before God.

The place where this healing took place is important. Samaria borders Galilee, and there is a “no man’s land” between them. Jesus is traveling “through the middle of Samaria and Galilee.” This could explain why the lepers include both Jews and Samaritans. Under normal circumstances, Jews would have nothing to do with Samaritans. But because these Jews and Samaritans have leprosy, they are drawn together by their common misery.

The place where this healing took place is important. Samaria borders Galilee, and there is a “no man’s land” between them. Jesus is traveling “through the middle of Samaria and Galilee.” This could explain why the lepers include both Jews and Samaritans. Under normal circumstances, Jews would have nothing to do with Samaritans. But because these Jews and Samaritans have leprosy, they are drawn together by their common misery.

Samaria had been the home of the ten tribes of Israel. When the Assyrians took the Israelites into exile in the 8 B.C., many Gentiles came to live in Samaria. Returning exiles inter-married with those Gentiles. As a result, Jews loathed Samaritans and considered them to be half-breeds. Jesus makes a hero of other Samaritans elsewhere in the Bible. The most familiar example is the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37). The Gospel of John also treats the Samaritan woman at the well as a positive figure (John 4:1-42).

Priests were responsible for diagnosing leprosy. The Torah provided specific guidelines for doing so (Leviticus 13:1-44). A diagnosis of leprosy was treated as a death sentence. It was much the same as a diagnosis of cancer or AIDS was only a few decades ago. The infected person was required to be isolated from all healthy people. The infected person had to shout “Unclean! Unclean!” when approached by a healthy person. (Leviticus 13:45-46; Numbers 5:2-3). The purpose was to prevent the infection from spreading. People also tended to regard leprosy as a sign of God’s judgment. That made most people less compassionate than they might otherwise have been. They believed that the person has brought suffering upon themselves.

Priests had great power. Once a priest judged a person to be unclean, that person was cast out from society. They could no longer live with their family. A leper was unable to hold a job or to engage in commerce. They begged to survive. To be restored to a normal life required a priest’s judgment that the person was no longer unclean. That was Jesus’ reason for sending these lepers to the priests. He wanted them to be restored to normal lives. Jesus also has another purpose. The lepers would bear testimony to the priests of His great healing power. When the priests judge the lepers to be clean, their judgments would authenticate Jesus’ Godly power.

The lepers were not healed immediately, but instead were healed as they obeyed Jesus’ command. No doubt, all ten lepers were thankful for their healing. They would be thankful to reenter their villages and workplaces. Thankful to go home to their families. In extreme gratitude, one man resisted the urge to go home and turned back to thank Jesus. Under the same circumstances, would we have stopped to give thanks? How often do you stop to thank God for your blessings? How often do we forget to thank God? Do you have an attitude of gratitude?

Ideas to Explore

Hold a group discussion on where we see the lack of gratitude today. Make a list for the group. Discuss how each person can try to demonstrate to others, their gratitude to God, Jesus, their parents, and their country.

Example of Historical Gratitude

The importance of the military chaplain was critical to the success of George Washington. Here is an excerpt from his field orders issued a mere 5 days after The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America was signed. Included in general orders issued July 9, 1776, was the following:

The Hon. Continental Congress having been pleased to allow a Chaplain to each Regiment, with the pay of Thirty-three Dollars and one third per month–The Colonels or commanding officers of each regiment are directed to procure Chaplains accordingly; persons of good Characters and exemplary lives–To see that all inferior officers and soldiers pay them a suitable respect and attend carefully upon religious exercises. The blessing and protection of Heaven are at all times necessary but especially so in times of public distress and danger–The General hopes and trusts, that every officer and man, will endeavor so to live, and act, as becomes a Christian Soldier defending the dearest Rights and Liberties of his country.

~ George Washington

James Caldwell was born in April 1734, in Cub Creek in Charlotte County, Virginia. He graduated from Princeton in 1759 and was ordained the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Elizabethtown in 1762. Caldwell served with the Third Battalion of Company No. 1, New Jersey Volunteers during the Revolutionary War, and was also Commissary to the troops in New Jersey. He was known as the “Fighting Chaplain.” On 25 January 1780, Reverend Caldwell’s church was burned down by the British. He moved his family to the parsonage at Connecticut Farms (now Union), New Jersey so that they might enjoy a safer life. Unfortunately, this was not to pass.

His journey into American history arrived at the end of a hundred-year journey for religious freedom. Caldwell’s ancestors had fled France after the fall of La Rochelle to Richelieu’s army in 1628. They migrated to Scotland, settling on an estate known as Cold Well, named for its cold well water (hence, the origins of the family name). Episcopacy was on the rise in Scotland, so they left for Ireland, sometime prior to 1649. There was also civil strife involving conflicts between Scotch and Irish. Parliament enacted economic restrictions along with limitations on Presbyterian activities. And then a famine began in 1725, combined to push the Caldwell’s out of Ireland into the New World.

His parents landed at New Castle, Delaware, on December 10, 1727. They made their way to the edge of the frontier in Charlotte County, Virginia. But their longing for religious freedoms were not quite within their grasp. The Church of England dominated that part of the county. So his father, John Caldwell, and others helped send a delegation to the Governor to seek permission to settle at Cub Creek and worship as Presbyterians. The petition was granted, and a church was organized in 1738. Services were held under a tree, and then a log church was built. By then James was part of the family, having been born on April 14, 1734.

Not much is known about James Caldwell’s youth. As part of a family living on the frontier in the early 1730s, he would have spent much of his time working: clearing land, feeding livestock, harvesting crops, cutting wood, hunting game and fishing. His father, as one of the leaders in the church (and in the community, serving as one of the first judges), would have conducted family devotions and taken his family to church. At some point during these years James felt the call of God upon his life and declared his desire to serve in the ministry. To help him prepare for college, he was sent to a local Classics School. In 1755, James entered the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). He graduated three years later with seventeen others, completing classes in Greek, Hebrew, rhetoric, logic, and so forth.

Following the procedures of the Presbyterian Church, James spent the next several months studying the Bible and preparing sermons under the tutoring of Dr. Samuel Davies. Davies was the president of the College of New Jersey. James was presented for licensure examinations on March 11, 1760. After delivering the last of three required sermons on September 17, he was ordained and began searching for a ministerial position. One such opening was in Elizabeth Town, New Jersey. During the eighteen months the church had been without a pastor, twenty men had applied for the office. Like those before him, he preached a trial sermon. His superior capacity for extemporaneous speaking, his animated, impressive, and captivating eloquence in the pulpit, and his fervent piety, rendered him the preferred candidate and James was offered the position. He was installed with a salary of one hundred and sixty pounds in March 1762. He was 27-years old. One year later, he added the last piece to the foundation of his life, marrying Hannah Ogden on March 14, 1763.

The next twelve years, he would grow as a pastor, affected by the looming shadows of war. The church at Elizabeth Town was one of the oldest in the country, having been constructed in 1667. His congregation was made up of laborers, shopkeepers, farmers, political figures, and future military leaders. By God’s grace, Caldwell’s energy and forceful preaching contributed to the growth of the congregation. They soon added a sixteen-foot extension to the rear of the church. By 1776, there were 345 “pew renters.” His days were filled with the standard pastoral duties. He would visit the sick, conduct weddings and funerals, attend to building matters, and help plant new churches. He preached two sermons every Sunday, pouring out his heart and soul: “As a preacher, he was unconsciously eloquent and pathetic; rarely preaching without weeping himself, and at times he would melt his whole audience into tears.”

To his church duties add denominational responsibilities. He maintained close connections with his alma mater, serving as a trustee. With Rev. John Witherspoon, he traveled through Virginia raising funds for the college. Caldwell would become a founder of several societies, including the verbosely titled “Society for the Better Support of the Widows and the Education of Children of Deceased Presbyterian Ministers in Communion with the Present Established Church of Scotland.” He served on a committee to promote missionary work among Indians. Caldwell was also on a committee to select, buy and distribute religious books and hymnals. He even sat on a committee to encourage missionary work in Africa and examine the church’s position on slavery. And he served as a faithful husband and father to ten children.

From the start of the American Revolution, Caldwell was an ardent supporter of the Revolution and was not ashamed to proclaim so from the pulpit. When the recriminations, protests and tensions finally broke out into flying musket balls and cannon fire on the fields of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, James Caldwell was ready. At a meeting of the Presbyterian Synod in May he again served with Rev. Witherspoon and was appointed to a committee to urge the Presbyterian churches to support the rebellion. These actions made the Presbyterians, and especially their clergy, targets for revenge. Back home he preached thunderous sermons, pleading for loyalty to the cause. Thirty-one officers and fifty-two enlisted men were to come out of the Elizabeth Town Presbyterian church. Though it was common for ministers to preach the cause of liberty, few stepped out of the pulpit into the line of duty. James Caldwell was one of the few.

Reverend Caldwell had already been working for the budding Revolution as a member of the Committees of Correspondence, which had helped disseminate news about anti-British activities prior to the war, and then once hostilities broke out helped recruit soldiers, materials, and arms. As chaplain, he went wherever his troops went. This meant that he was able to minister, not only to the soldiers, but also to the residents of nearby towns. He preached, held baptisms and too often, funerals. As he had in his hometown, he gained a reputation for his preaching. People of the time wrote: “His countenance has a pensive, placid cast; but when excited, was expressive of high resolution and energy.” It was said that his voice became sweet and musical, and yet so strong that, when needful, he would make himself heard above the notes of the fife and drum.

The American War for Independence was on the edge of disaster entering 1780. More than 600 had deserted Washington’s army in Morristown, N.J., helped along by a more severe winter than that suffered at Valley Forge. Pockets of mutiny had sprung up throughout the winter and into the spring. Then, in May 1780, Charleston, S.C., fell to British General Charles Cornwallis. For Reverend James Caldwell, the year of 1780 would prove to be a year of suffering and sorrow for the soon to become the “Fighting Chaplain.” First, a night raid by the British against the town left the courthouse and Presbyterian Church burnt to the ground. Caldwell lost many personal papers, as well as church records and documents.

On 6 June 1780, British Lieutenant General Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen crossed over from Staten Island into New Jersey with six to seven thousand German soldiers. He was on his way to Springfield, but first there was a skirmish at Connecticut Farms where Caldwell had earlier relocated his family. When word reached the town of the invasion, Caldwell decided to move his family once again. His wife, however, did not wish to leave. It is speculated that she did not want to travel with the young children, or that she felt safer in her house than out on the open road. Whatever the reason, she stayed behind while the older children were sent to friends in another town. James then rode off to join his brigade. It was a fateful decision. While the noises of war, whizzing musket balls, running horses, shouting troops, filled the air, Hannah made a few nervous preparations. She hid several items in a bucket, lowering them into the well; she pocketed some silverware. She put on nicer clothes, in case she would have to address a British officer, and then retreated to her bedroom with her youngest children. “Mrs. Caldwell felt confident that no one would have the heart to do injury to the inhabitants of the house. Again and again she had said, ‘They will respect a mother.’” She was wrong. As the British marched into town, a redcoat jumped the fence, came up to the house and shot through the window, splattering glass, killing Hannah Caldwell with a ball through the chest. Other soldiers poured into the house. They pilfered her pockets, looted the house, and took five hundred sermons James had written out in longhand. Her body was removed before they torched the home. For several hours she was left exposed in the open air, clothes torn and disheveled, until neighbors took her in. The day ended with the British setting fire to the village.

On 6 June 1780, British Lieutenant General Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen crossed over from Staten Island into New Jersey with six to seven thousand German soldiers. He was on his way to Springfield, but first there was a skirmish at Connecticut Farms where Caldwell had earlier relocated his family. When word reached the town of the invasion, Caldwell decided to move his family once again. His wife, however, did not wish to leave. It is speculated that she did not want to travel with the young children, or that she felt safer in her house than out on the open road. Whatever the reason, she stayed behind while the older children were sent to friends in another town. James then rode off to join his brigade. It was a fateful decision. While the noises of war, whizzing musket balls, running horses, shouting troops, filled the air, Hannah made a few nervous preparations. She hid several items in a bucket, lowering them into the well; she pocketed some silverware. She put on nicer clothes, in case she would have to address a British officer, and then retreated to her bedroom with her youngest children. “Mrs. Caldwell felt confident that no one would have the heart to do injury to the inhabitants of the house. Again and again she had said, ‘They will respect a mother.’” She was wrong. As the British marched into town, a redcoat jumped the fence, came up to the house and shot through the window, splattering glass, killing Hannah Caldwell with a ball through the chest. Other soldiers poured into the house. They pilfered her pockets, looted the house, and took five hundred sermons James had written out in longhand. Her body was removed before they torched the home. For several hours she was left exposed in the open air, clothes torn and disheveled, until neighbors took her in. The day ended with the British setting fire to the village.

James was with General Lafayette on the heights near Springfield. When he saw the smoke he said, “Thank God! The fire is not in the direction of my house.” He was wrong and soon overheard the truth from returning soldiers. He rushed back to the town to find his wife, and the mother of his ten children, gone. The funeral was held that afternoon. Following the death of his wife, Caldwell made provisions for his children then continued his duties. He kept on preaching and attending to the troops. The news of the murder lit up the country with indignation. For James, there was no time to mourn. Indeed, in a mere two weeks he would be riding the countryside, sounding the alarm of the British advancement on Springfield.

As Knyphausen marched down the main road, he met American Colonel Israel Angell, bunkered down in an apple grove across the Rahway River. The Redcoats moved up and let loose a furious volley, using 6 artillery pieces. The broadside tore off chunks of the apple trees and killed the American regiment’s lone artillery gunner. Despite the crucial loss, Colonel Angell held off a force five times larger than his own for 25 minutes. During the heat of the battle, the American militia began to run out of wadding. This is the paper used to roll powder and ball, thus sealing the barrel so they could continue shooting at the enemy. Reverend James Caldwell sprang into action. Caldwell was said to have dashed into a nearby Presbyterian Church, scooped up as many Watts hymnals as he could carry, and distributed them to the troops, shouting “put Watts into them, boys.” The boys responded and poured lead into the oncoming enemy.

As Knyphausen marched down the main road, he met American Colonel Israel Angell, bunkered down in an apple grove across the Rahway River. The Redcoats moved up and let loose a furious volley, using 6 artillery pieces. The broadside tore off chunks of the apple trees and killed the American regiment’s lone artillery gunner. Despite the crucial loss, Colonel Angell held off a force five times larger than his own for 25 minutes. During the heat of the battle, the American militia began to run out of wadding. This is the paper used to roll powder and ball, thus sealing the barrel so they could continue shooting at the enemy. Reverend James Caldwell sprang into action. Caldwell was said to have dashed into a nearby Presbyterian Church, scooped up as many Watts hymnals as he could carry, and distributed them to the troops, shouting “put Watts into them, boys.” The boys responded and poured lead into the oncoming enemy.

Caldwell’s legendary deed did not turn the course of battle that day. At best, it delayed the invasion of Springfield by a few minutes. But the event stirred such patriotic fervor that those who saw it passed it on to succeeding generations until Washington Irving recorded it in his biography of George Washington. For the “Fighting Chaplain,” it was one more selfless act in a life full of courage, patriotism and service to others and God.

On Nov. 24, 1781, Reverend Caldwell went to greet a lady named Beulah Murray, who was scheduled under a flag of truce to visit some relatives. She had rendered service to American prisoners in the prison ships in New York and was held in esteem. He drove a chaise (thought to be a light open two-wheeled carriage) to Elizabeth Town Point along Newark Bay to bring her to town. He could not find her. He went on board the sloop. Upon debarking with a bag, a sentry ordered him to stop. American authorities were battling smugglers of British goods from New York to New Jersey. Strict orders had been issued to all sentries to look for illicit trading. After walking Ms. Murray to his carriage, he returned to the boat, to retrieve a package that was left behind. On the return to his carriage, an American sentinel, named James Morgan, challenged him, asking what was in the package. Caldwell attempted to proceed to the proper officer with the package, but as he attempted to move away, the sentinel, just relieved from duty, fired his musket, killing the Reverend Caldwell with two balls. Caldwell had stopped, but the sentry shot him anyway. James Caldwell, the “Fighting Chaplain,” dropped dead. The sentry, James Morgan, was hanged for murder on January 29, 1782, in Westfield, New Jersey, amid rumors that he had been bribed to kill the chaplain.

There were ten orphaned children of Hannah and James Caldwell, all who were raised by friends of the family. Caldwell lived a full life. One marvels at the breadth of his service to his country and his Savior. It is easy to imagine that he might have gone on to serve his country in the new Republic as one of the Founding Fathers. What distinguished James Caldwell from most other clergymen of his day is that, while he continued his ministerial activities during the struggle for freedom, he also performed other services demonstrating his devotion to the patriot cause. Others, from many different walks of life, exhibited the same devotion and made sacrifices. But James Caldwell, as the minister who stood with the fighting men during battle, who rallied others to continue the war when the situation appeared hopeless, who sacrificed the life of his wife when he considered it his duty to be with the troops, and who met his own death while performing a helpful service for someone else, stands out above many others. The Reverend James Caldwell and his wife were buried in the churchyard of the First Presbyterian Church in Elizabethtown. A monument to him in Elizabeth, New Jersey was dedicated in 1846.

Ideas to Explore

This section might be an opportunity for a “meet and greet.” Consider inviting a military chaplain, a sheriff office chaplain, a hospital chaplain and possibly a prison chaplain to gather with your group. Have an informal question and answer session.

- How does each role, the military, the sheriff’s office, the hospital, and the prison differ?

- What made them choose that job?

- What are their duties?

- What is it that they love?

- What is hard?

Let the group interact and ask questions.

Examples of Historical Gratitude Occurring in Florida

The first public police force was created in Boston in 1838 in response to the urging of private businesses. Merchants wanted a public system to fund the protection of their wares, which up to that point were secured by private security. This concept spread and by the late 1880s all major cities maintained public police forces. America’s emphasis on state and local government autonomy from the federal government leads to a great deal of diversity in policing systems across cities, counties, and states. A single city can be patrolled by multiple policing agencies with overlapping responsibilities.

In addition to organizational diversity, the physical boundaries of police jurisdictions are also diverse. Originally, police precinct boundaries aligned with electoral boundaries. This changed in 1929 in response to the findings of former President Herbert Hoover’s Wickersham Commission. The commission called for redistricting precincts, so they no longer fell on political lines, thereby reducing politicians’ ability to influence or exploit police forces in their jurisdictions. Today, police forces are a major part of local government operations and the second largest budget item after education.

There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the United States. There are 906,037 full-time law enforcement employees and 94,275 part-time employees2https://usafacts.org/articles/police-departments-explained. State and local police employment decreased from a high of 1,019,246 officers in 2008 to 1,000,312 officers in 2019. Police account for 6% of all full-time employees for state and local governments. Unfortunately, current statistics are difficult to establish. According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2008 Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, Florida had 387 law enforcement agencies employing 46,105 sworn police officers, about 250 for each 100,000 residents.

Sworn officers all take a similar oath. They swear to uphold the Constitution, both Federal and State, and to seek God’s help in the job they do.

“I, _____________________, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of ______________________ for the (town/city/state) of ____________________________ and will to the best of my ability faithfully execute the oath of my duties as ____________________________, and swear that I will preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States, the laws of the State of _____________________ and the ordinances of the Town/City of ____________________________, so help me God.”

The word “police” comes from the Greek politeia, meaning government, which came to mean its civil administration. The more general term for the function is law enforcement officer or peace officer. A sheriff is typically the top police officer of a county, with that word coming from the person enforcing law over a shire. A person who has been deputized to serve the function of the sheriff is referred to as the deputy. Police officers are those empowered by government to enforce the laws it creates. In The Federalist collection of articles and essays, James Madison wrote: “If men were angels, no Government would be necessary“. These words apply to those who serve government, including police.

Police officers are generally charged with the apprehension of suspects and the prevention, detection, and reporting of crime, protection and assistance of the public, and the maintenance of public order. As Godly people know, the world is a sinful place. Drugs, murder, crimes of every type of plague humankind. The role of a police officer is to protect those who follow the law. Just to create an appreciation for how difficult the role is, here are the types of police in the State of Florida:

- State Agencies such as Highway Patrol, FWC Wildlife Commission, State Park Services, Agricultural and Alcohol Enforcement, Fire Marshal, Lottery, Financial Fraud, Department of Corrections, State Attorney’s Office, and more.

- County Agencies for each of Florida’s 67 counties

- City Agencies for each of Florida’s major cities

- University and College Agencies

- School District Agencies

- Airport Agencies

- Native American Tribe Agencies

Our society needs our police and must maintain respect for the important role they play in keeping all of us safe and secure. Think about what we gain when we are safe and secure. It is what the founding fathers envisioned in the Preamble to the Constitution – “to secure the blessings of liberty for ourselves and for our posterity.” The gratitude must be from us to them. This can only be fully understood by taking a field trip to the American Police Hall of Fame & Museum in Titusville, FL. It is the nation’s first national law enforcement museum and memorial dedicated to American law enforcement officers.

Ideas to Explore

Ideas to Explore

The American Police Hall of Fame & Museum, founded in 1960, is the nation’s first national law enforcement museum and memorial dedicated to officers killed in the line of duty. The Memorial lists over 10,300 officers who were killed in the line of duty. Their names are permanently etched on the Memorial’s walls. Names are added to the wall once a year prior to Law Enforcement Memorial Day. Explore a collection of historic and futuristic police cars. Or you can have your picture taken in a replica electric chair or behind the bars of a realistic prison cell. You can find out how law enforcement agencies do their forensic investigations and how crime scenes are analyzed.

The American Police Hall of Fame & Museum, founded in 1960, is the nation’s first national law enforcement museum and memorial dedicated to officers killed in the line of duty. The Memorial lists over 10,300 officers who were killed in the line of duty. Their names are permanently etched on the Memorial’s walls. Names are added to the wall once a year prior to Law Enforcement Memorial Day. Explore a collection of historic and futuristic police cars. Or you can have your picture taken in a replica electric chair or behind the bars of a realistic prison cell. You can find out how law enforcement agencies do their forensic investigations and how crime scenes are analyzed.  The Museum, through interactive displays, simulators and nearly 11,000 artifacts, educates the public about the history and current trends in American law enforcement. Students can learn about safety, science, forensics and much more!

The Museum, through interactive displays, simulators and nearly 11,000 artifacts, educates the public about the history and current trends in American law enforcement. Students can learn about safety, science, forensics and much more!

The Museum is located at:

6350 Horizon Dr.. Titusville, FL 32780 Tel: 321.264.0911 PoliceInfo@aphf.org

Practicing Acts of Gratitude

The way to show gratitude is to tell others about Jesus. Here would be an excellent place to work on thinking through why a person trusts God, loves Jesus and is happy to tell others about their faith.

A testimony is a simple thing: What was your life like before you accepted Jesus into your life? How did you come to make that decision? How has your life changed? Write it, share it with each other. Keep it your testimony, in your words, in your style.

- 1NIV New International Version Translations

- 2https://usafacts.org/articles/police-departments-explained