Life in the Colonies

There were 16 colonies in existence just prior to the American Revolution. We all know our list of the major 13 colonies: The New England colonies were Massachusetts Bay Colony (which included Maine), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut; the Middle Colonies were New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware; and the southern colonies of Georgia, Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia, and North Carolina. Florida would add two additional colonies called East Florida and West Florida. Some also include Canada as the 16th colony because of its influence on trade and the American Revolution.

There were 16 colonies in existence just prior to the American Revolution. We all know our list of the major 13 colonies: The New England colonies were Massachusetts Bay Colony (which included Maine), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut; the Middle Colonies were New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware; and the southern colonies of Georgia, Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia, and North Carolina. Florida would add two additional colonies called East Florida and West Florida. Some also include Canada as the 16th colony because of its influence on trade and the American Revolution.

While there were cities, there was also a large rural population. Life was hard and for children, there were chores. Gathering wood daily, fetching water with a pail, feeding livestock and harvesting food would have filled their day. For those lucky enough to live in a town, there was school with a focus on reading and writing. Leisure time was minimal, games were simple.

Hands-On Opportunity

Having the teachers dress as colonials is always a big hit. Buckle shoes, breaches, waist coats, frocks, simple shirts make up the dress for men. For ladies, dress could have been simple as a dresses, skirts, bodices, aprons, hats, gloves, capes and petty coats. If you cannot purchase them and wear them, pictures help show the styles of the times. Other items to include in a show and tell would be lanterns, candles, cooking utensils, homemade soap, currency and coins and writing instruments such as feather quills. This is totally dependent upon the volunteers you can find, people from the period camping and reenacting communities to bring items that can be passed around. Reproduction currency and coins are also a good item to use.

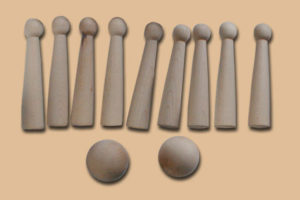

Nine Pin

One of the greatest areas of interest are toys. Dolls were handmade, action toys were simple wood objects, hoops, jacks, Jacob’s Ladder, swords, small wooden bows and toy arrows. There still are period wood smiths where you can find samples of 18th century children’s toys. You might want to make the point that “no batteries” are necessary. Setting aside time to play with some of the toys will help reinforce the simplicity of colonial times. How many children today even know what a spinning top is or looks like.

Teaching Opportunity

There is one point to all your demonstrations, life was hard for children. No TV, no electricity, no phones. You might try taking a pail and putting some rocks in it. The average pail holds about 20 pounds of water. Ask each young patriot to carry it across the room. Now tell them that it was their job to do these three times a day and, by the way, the creek is a half a mile from their cabin.

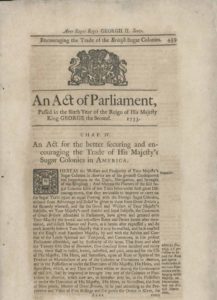

The Molasses Act of 1733

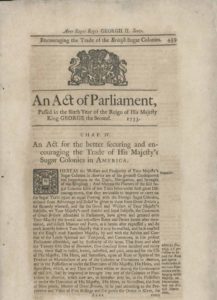

Molasses Act

Government policies, trade, even wars are often underpinned by the things people need and use. During the early 1700’s molasses was an important trade commodity. Made from the juices of sugar cane, the primary purpose for molasses was to produce rum. A large colonial molasses trade existed between the colonies in New England, the Middle colonies and the French, Dutch, and Spanish West Indian possessions. Molasses from the British West Indies, used in New England for making rum, was priced much higher than its competitors. New England colonies also had no need for the large quantities of lumber, fish, and other items offered by the other colonies in exchange.

Rather than prohibit the colonies from trading with the non-British islands to protect trade and profits, the British Parliament passed a prohibitively high tax on the colonies for the import of any molasses from any islands not part of the British Empire. The impact then on the average colonist was to see the price of certain products like rum remain high. This tax would begin the cycle that eventually would lead our colonies to separate from Britain’s control. As a learning opportunity, the concept of a tax to influence and control citizens is introduced.

While the Molasses Act may seem to predate any wars, it represents how Great Britain viewed the colonies as not much more than a source of funds.

Hands-On Opportunity

Purchase a jar of molasses. Pour it out into a bowl so the youth can see its brown color and viscosity. Pass out popsicle sticks and let them dip in to taste it. Keep a trash container with a liner nearby. Most will not like the taste.

Teaching Opportunity

Take time to have a snack break. Pass out coupons as colonial currency. Each gets the same amount. Now offer a nice snack that they must purchase with their colonial currency. Have two piles of snacks. Divide the class into two groups assigning each group to pick from only one of the piles. As they prepare to make their purchase, place a TAX on pile one so they can only get one snack for their money and pile two will give them two snacks. All snacks should be the same. The point will be to ask those who only could spend their money and get one snack to admit, it wasn’t fair. That is how the colonists felt too. Taxes are often used to control the behavior of those required to pay it.

The French and Indian War

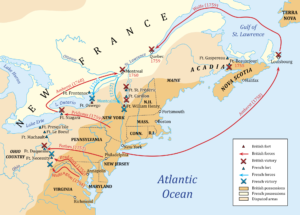

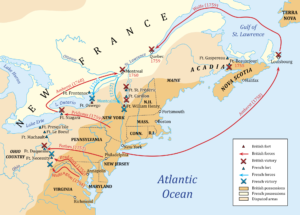

The French and Indian War as called by our colonists, was the beginning of the change of attitude between Great Britain, France and the colonies. By 1700, there were 250,000 people in the colonists. But by 1750, that number had grown to 1.25 million. In Europe, this war was called the Seven Years War and was the first truly global conflict, a world war. By 1754, Prussia, Austria, Britain, France and Spain were involved with the hostilities spreading to the colonies. Eventually, the English dominated the colonial outposts but the cost to Great Britain was staggering. The British Government had borrowed heavily from British and Dutch bankers to finance the war, and therefore the national debt would lead to a series of taxes all aimed at paying for the conflict. Part of the great injustice called “Taxation without Representation” would be the fact that much of costs (debt) of the Seven Years War would come from the European side of the conflict. However, the colonies were to carry a much higher burden of repayments, more than their perceived fair share. The French and Indian War was the colonial conflict with France over expanding westward into Indian territories.

It is important to note that the principle trading partner for the colonies was the East India Tea Company. This company held a privileged position where special rights were granted to them, giving the East India Tea Company exclusive rights (monopolies) aimed at driving out any competing nations. Virtually all cotton, silk, indigo dye, salt peter, tea and opium were under the control of this company. Yes, drugs were a part of our colonies early history. No colony could import or export products unless the East India Tea Company was involved. Colonists were paying much more for their products and receiving much less for the products they produced.

It is important to note that the principle trading partner for the colonies was the East India Tea Company. This company held a privileged position where special rights were granted to them, giving the East India Tea Company exclusive rights (monopolies) aimed at driving out any competing nations. Virtually all cotton, silk, indigo dye, salt peter, tea and opium were under the control of this company. Yes, drugs were a part of our colonies early history. No colony could import or export products unless the East India Tea Company was involved. Colonists were paying much more for their products and receiving much less for the products they produced.

The colonies were very interested in raising their own armies and funding the French and Indian War. Despite petitions to King George II, offers were declined. The king was suspicious and felt that such armies after the war could be turned against Great Britain. The best that our colonies could bargain for was to assist the British in their war. British armies would demand horses, feed, food, wagons and shelter from the colonists but usually deny them the right to defend themselves. The lack of an ability to protect themselves would fester in the minds of America’s early leaders and influence the timing of the American Revolution.

Hands-On Opportunity

This period of history is heavily influenced by the expansion west into the Ohio Valley and much fighting between tribes living in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Canada. Some Indians aligned with the French and others with the English. It would be an excellent place in your program to introduce the American Indian culture. For Hands-On, it would be suggested that beading, leather clothing, bows and arrows, are made available for the youth to see and handle. Much will depend upon the resources of your adult leaders and what they might be able to bring to the Patriot Camp.

Learning Opportunity

Battlefield Scene

This was a brutal time in American History. It is what set in the minds of the colonists that they must be able to defend themselves. The colonies were not only under pressure from France and its native partners, but the British soldiers took what they wanted. The colonies had virtually no rights of freedom or defense.

Have the children discuss how they would feel if they had to give up their home, their food, to a stranger (British Soldiers) and be left with nothing. This introduces the concept of quartering.

The Great Debt

By the end of the French and Indian War, Britain was in debt. The British thought the colonists should help pay for the cost of their own protection. The war had cost the British treasury £70,000,000 and doubled their national debt to £140,000,000. In today’s US currency, Britain’s national debt was equivalent to over 5 billion dollars. – There is a simple lesson to this segment, too much debt is not good, and debt must always be paid back. The debt would generate oppressive government taxes and help lead to the American Revolution. Depending upon the age of the students, this opens an opportunity to discuss the National Debt of America

In the next years, the following taxes were levied by Great Britain against the colonies. There are too many to cover in a short program. The taxes below were selected as a representative list of those most notable in history.

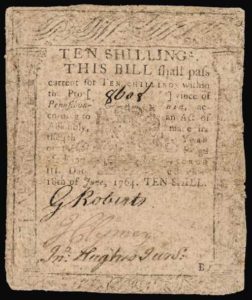

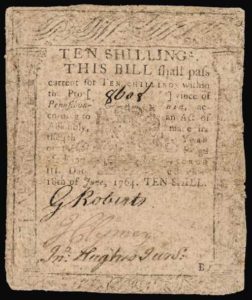

The Currency Act – 1764

1764 Currency

The Currency Act is one of many several Acts of the Parliament of Great Britain that regulated paper money issued by the colonies of British America. The first such Act was in 1751. The Acts sought to protect British merchants and creditors from being paid in depreciated colonial currency. The policy created tension between the colonies and Great Britain and would be cited as a grievance by colonists early in the American Revolution.

From the origin of the colonies, they all struggled with the development of an effective medium of exchange for goods and services. After depleting most of their existing monetary resources through imports, the first settlers strained to keep money in circulation. They could not find a suitable medium of exchange in which the value did not depreciate. The colonists generally employed three main types of currency. The first was commodity money, using the currency of a given region as a means of exchange. The second was gold or silver money. Lastly, paper money, issued in the form of a bill of exchange or a bank note, mortgaged on the value of the land that an individual owned.

Each year, the supply of gold and silver in the colonies decreased due to international factors making it ineffective as a means of exchange for day-to-day purchases. Colonists frequently adopted a barter system to acquire the goods and services they required. Essentially, this method also proved to be ineffective and a commodity system was adopted in its place. Tobacco was used as a monetary substitute in Virginia as early as 1619. A major shortcoming of this system was that the quality of the substitutes was inconsistent. The poorer qualities ended up in circulation while the finer qualities were inevitably exported. This commodity system became increasingly ineffective as colonial debts increased.

This Act restricted the issuing of paper money and the establishment of new public banks by the colonies in New England. These colonies had issued paper money known as “bills of credit” to help pay for military expenses during the French and Indian Wars. Because more paper money was issued than what was taxed out of circulation, the currency depreciated in relation to the British pound sterling. The resultant inflation was harmful to merchants in Great Britain, who were forced to accept the depreciated currency from colonists for payment of debts.

The Act limited the future issuance of bills of credit to certain circumstances. It allowed the existing bills to be used as legal tender for public debts (i.e. paying taxes) but disallowed their use for private debts (e.g. for paying merchants).

Hands-On Opportunity

Depending upon the grade levels of the students, this topic can be as simple as passing around samples of the various coins, currency and notes. Reproductions are readily available. For older students, you may consider depreciating the values of the incentive you have been using for “good questions.” You can always re-appreciate them at the end of your program as a reward.

Learning Opportunity

Paper money has no intrinsic value. It is used with complete trust in the issuer. That is why inflation, monetary easing, Federal banking policies impact all of us. The Currency Act by the British Government recognized that the monetary policy of the colonies along with their apportioned debt for the French and Indian War was lowering the value of colonial currency. Today’s fancy word for it is inflation. Inflation impacts the costs of goods and services.

The Sugar Act – 1764

Cone Sugar

Sugar Nippers

The Molasses Act was set to expire in 1763. The Commissioners of Customs anticipated greater demand for both molasses and rum because of the end of the French and Indian war and the acquisition of Canada. They believed that the increased demand would make a sharply reduced rate both affordable and collectible. When passed by Parliament, the new Sugar Act of 1764 halved the previous tax on molasses. In addition to promising stricter enforcement, the language of the bill made it clear that the purpose of the legislation was not to simply regulate the trade (as the Molasses Act had attempted to do by effectively closing the legal trade to non-British suppliers) but to raise revenue.

The new act listed specific goods, the most important being lumber, which could only be exported to Britain. Ship captains were required to maintain detailed manifests of their cargo and the papers were subject to verification before anything could be unloaded from the ships. Customs officials were empowered to have all violations tried in vice admiralty courts rather than by jury trials in local colonial courts, where the juries generally looked favorably on smuggling as a profession. New England ports especially suffered economic losses from the Sugar Act as the stricter enforcement made smuggling molasses more dangerous and risky.

Hands-On Opportunity

At this time in the colonies, sugar was brown and often dried into cones. Cone sugar is still available today in markets that supply ethnic foods to descendants from the Caribbean islands. It was expensive and typically kept in wooden boxes. A form of scissors, called sugar nippers, was used to chip off pieces of the cone for use in their tea. Fill a small container with chips made by a sugar nipper and let the class taste what sugar was like during the colonial period.

Learning Opportunity

High taxes, regulations frequently cause unexpected consequences. This is a good time to introduce the idea of artificial price controls, smuggling and the connection to crime. When a government attempts to force purchasing or selling goods/services from only one supplier, that is a monopoly. When the item is something that people really want like sugar for making rum, laws are ignored, and illicit industries are created. Moonshine, the prohibition of alcohol, even the war on drugs are contemporary examples of this issue.

The Quartering Act – 1765

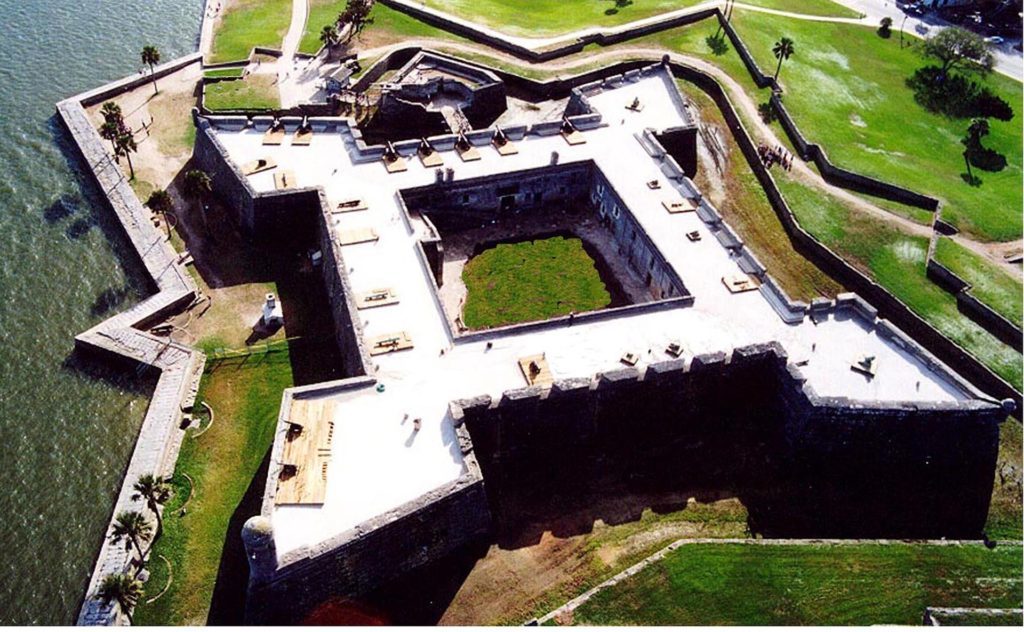

The Province of New York was the headquarters of British troops remaining in the colonies after the end of the French and Indian War. Britain’s Parliament had passed an Act to provide for the quartering of British regulars, but it expired on January 2, 1764. The result was the Quartering Act of 1765, which went far beyond the previous law. No standing army had been kept in the colonies before the French and Indian War, so the colonies asked why a standing army was needed after the French had been defeated in battle.

The Quartering Act, signed May 15, 1765, provided that Great Britain could house its soldiers in American barracks and public houses, as granted by the Mutiny Act of 1765, but if its soldiers outnumbered the housing available, could quarter them in “inns, livery stables, ale houses, victualing houses, and the houses of sellers of wine and houses of persons selling of rum, brandy, strong water, cider or metheglin”, and if numbers required in “uninhabited houses, outhouses, barns, or other buildings.” Colonial authorities were required to pay the cost of housing and feeding these troops. Simply stated, the British Army was granted the right to colonial private property without fair compensation to the owner.

Learning Opportunity

The term Quartering is not common in society today. However, when the lessons begin to cover the grievances of the colonists written into “The Declaration of the Thirteen United States of American,” the background is helpful. This is simply a discussion about rights. Do citizens have the right to their own property? Under King George III and the British government, no colonist had such rights. Even today, there is much sensitivity to this issue when subjects like eminent domain are considered. The question for any group of students is whether circumstances could exist where a person’s property could be taken without fair compensation?

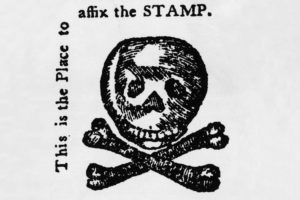

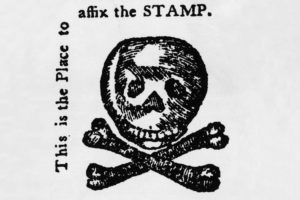

The Stamp Act – 1765

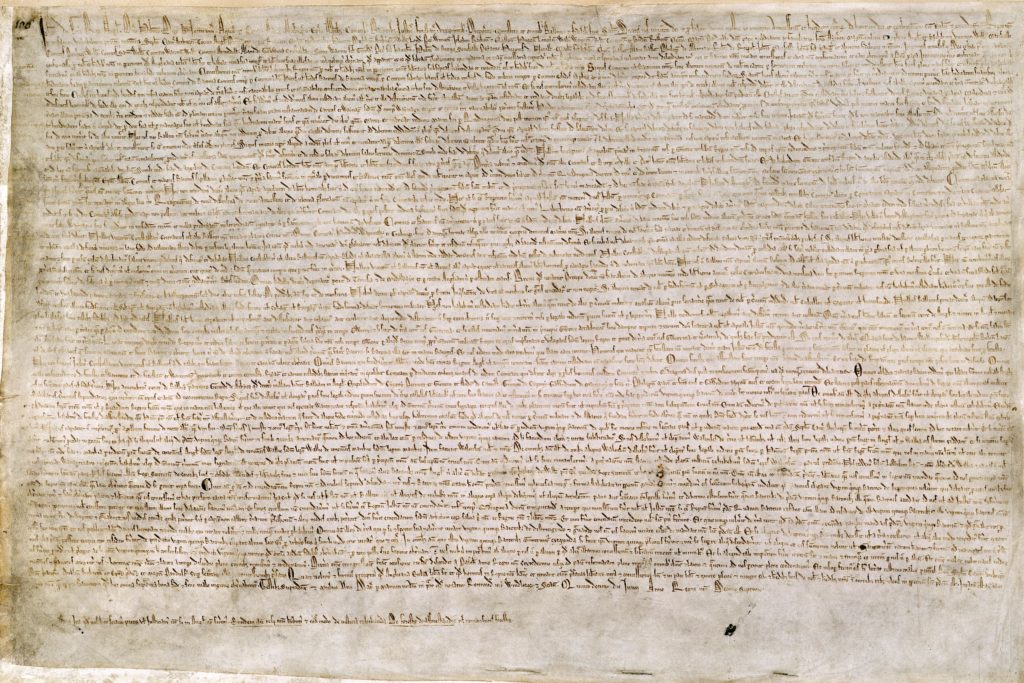

Stamp Act Stamp

Also called “Duties in American Colonies Act 1765,” it was a direct tax imposed on the colonies and required for all printed materials produced in London. These products were required to carry an embossed revenue stamp. This was significant because of the scarcity of printing presses in the colonies and the heavy dependence on Britain for such products. Things like legal documents, magazines, newspapers and other types of paper products were affected. The tax had to be paid in valid British currency, not in colonial paper money. Again, the purpose was to help pay for the British troops stationed in North American after the British victory in the French and Indian War. Since colonists were the beneficiary of this military presence, the British government felt that the colonies should be required to pay for a portion of that cost.

Hands-On Opportunity

Today, many suppliers of period reproduction items from the 18th century carry playing cards. On the box of cards is an embossed revenue stamp. It is often fun to pass around the cards, so the idea of a tax stamp can be brought to life.

Learning Opportunity

The significance of the Stamp Act was to spread the anger to almost every colonist. While the price of rum affected some, even the higher costs of imported products, paper products such as magazines, newspapers, even playing cards impacted every family in some way. This one Act might be viewed as the very tipping point of the Revolution. Rebellion against King George III escalated quickly. While the Stamp Act itself was ended rather quickly, the damage was done. Too many colonists were ready to break ties with Britain.

Townshend Acts – 1767

The Townshend Acts (also called the Intolerable Acts) were a series of laws passed by the British Parliament specifically targeting trade in the colonies. They were named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer , who proposed the program. Most historians agree that there were five laws: The Revenue Act of 1767; the Indemnity Act; the Commissioners of Customs Act; the Vice Admiralty Court Act and the New Your Restraining Act. The purpose of the Townshend Acts was to raise revenue in the colonies to pay the salaries of governors and judges so that they would be independent of colonial influence. Their roles were to enforce compliance with trade regulations, to punish New York for failing to comply with the Quartering Act and to establish the principle that the British Parliament has the right to tax the colonies. The Townshend Acts met with resistance prompting occupation of Boston by British Troops.

Learning Opportunity

There is a lot of detail in the Townshend Acts and it is not recommended that you go through this tax by tax. The principle that evolved from this was the cry of “Taxation Without Representation.” Colonists had no input to whether the taxes were fair or not. They could not vote and pick their government leaders or their judges. Just a good discussion on the present system of elections and the right of American citizens to elect their officials is appropriate. Additionally, you might consider the introduction of present “rule-making,” the granting of rights to non-elected officials to create rules (laws) we use in the United States. The question to discuss might be how today’s modern rulemaking is like the Townshend Acts.

British Troops Occupy Boston – 1768

The Massachusetts House of Representatives began a campaign against the Townshend Acts by sending a petition to King George III asking for the repeal of the Townshend Revenue Act. This would become something known as the “Circular Letter,” going to other colonial assemblies asking them to join the resistance. In Great Britain, Lord Hillsborough, the newly appointed office of Colonial Secretary became alarmed by the actions of Massachusetts. In April of 1768 he sent a letter to colonial governors in America, instructing all colonial assemblies to be dissolved along with rescinding the Circular Letter. None complied.

In May of 1786, the HMS Romney arrived to strengthen the British Military Presence in Boston. Upon arriving, the ship Liberty was seized on suspicion of smuggling. The owner of the Liberty was John Hancock. Numerous colonial sailors were being forced into the British navy and anger began to permeate the colonies. On October 1, 1768, the first of four regiments of British troops arrived in Boston. Boston was now under siege.

Learning Opportunity

The experiences in 1768 led colonists to understand the importance of protecting peaceful assembly and the ability to partition a government with a complaint. What did the King do? He attempted to dissolve the colonial governments and send troops. Later, as students look at the complaints of colonists and our Bill of Rights, we can begin to understand why we became a Constitutional Republic, protecting certain “unalienable rights.”

The First Death of the American Revolution – February 22, 1770

Christopher Seider (or Snider) (1758—1770) was the first American killed in the political strife that later would become the American Revolution. Only twelve years old at the time, Seider was shot and killed in Boston on February 22, 1770. His funeral became a major political event, with his death heightening tensions that erupted into the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770.

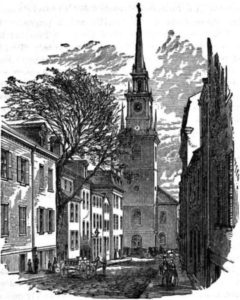

The Customs House has been renamed “Butcher’s Hall” and a gun can be seen firing from a window -an oblique reference to the death of Seider in Paul Revere’s most famous etching of the Boston Massacre.

The Customs House has been renamed “Butcher’s Hall” and a gun can be seen firing from a window -an oblique reference to the death of Seider in Paul Revere’s most famous etching of the Boston Massacre.

Seider was born in 1758, the son of poor German immigrants. On February 22, 1770, he joined a crowd mobbing the house of Ebenezer Richardson located in the North End, Richardson was a customs service employee who had tried to disperse a protest in front of Loyalist merchant Theophilus Lillie’s shop. The crowd threw stones which broke Richardson’s windows and struck his wife. Richardson tried to scare them by firing a gun into the crowd. Seider was wounded in the arm and the chest but died that evening. Samuel Adams arranged for the funeral, which over 2,000 people attended. Seider is buried in Granary Burying Ground along with the victims of the Boston Massacre which occurred just 11 days later.

Richardson was convicted of murder that spring, but then received a royal pardon and a new job within the customs service, claiming he had acted in self-defense. This became a major American grievance against the British government.

The Boston Massacre – 1770

Boston Massacre by Paul Revere

The Boston Massacre is one of the most noted events in the history of the American Revolution. Here we are introduced to several people, Paul Revere and John Adams. The Boston Massacre occurred on March 5, 1770. By now, Boston was an occupied city. The civil unrest had prompted King George III to send troops to keep down any thoughts of rebellion. On a cold night, a squad of British soldiers, were being pressed by a heckling, snowballing crowd, let loose a volley of shots. Three persons were killed immediately and two died later of their wounds. Among the victims was Crispus Attucks, a man of black parentage. The British officer in charge, Capt. Thomas Preston, was arrested for manslaughter, along with eight of his men.

A young Boston attorney, John Adams, came to their defense after understanding what had transpired that night. After a trial with a jury seated which were colonists, all were acquitted. This did much to show the people of Boston that the rule of law works. However, we now introduce Paul Revere, a talented silversmith and engraver. More importantly, an active member of the “Sons of Liberty.” Revere creates a printing plate of a scene, depicting the cold-blooded killing of 5 colonists. The printing plate would be used to produce thousands of posters that quickly spread through the colonies. Anger grew, and this etching is considered a principle catalyst to the Revolution.

Hand-on Opportunity

The etching is readily available online and can be found in both a black and white (original) and color versions. It is of a scene near the Custom House and Faneuil Hall in Boston where the shootings took place. Most students, today, understand social media. It drives opinion at the speed of light. There was, however, social media during the colonial period. For this part of the study, consider researching and finding the many samples of posters that were used expressly for altering public opinion. Paul Revere’s etching is just one appropriate example. Pamphlets were also used. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense pamphlet is still the most widely distributed printing based on population size in American History. It is still in print today. Having samples of these items, maybe even a sample page or two of Ben Franklin’s newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette will begin to show students the power behind the pen.

Teaching Opportunity

This would be a good time to discuss how the media, simple printed pages delivered by horseback have evolved into interactive social media. The question to ponder is whether we still see misrepresentations of newsworthy events? How can we know the truth? While Paul Revere misrepresented the event and angered patriots who then were willing to go to war, was this OK or not? To be considered is: impact on individual rights; the dangers of activism; the benefits of applying the law equally to all people; whether a cause can be great enough to ignore the truth?

Tea Act – 1773

Brick Tea

This is another one of the defining moments in American history. Colonists react dramatically to the oppression from Great Britain, ultimately triggering the Revolution. The Tea Act of 1773 was one of several measures imposed on the American colonists by the heavily indebted British government in the decade leading up to the American Revolutionary War. The act’s main purpose was not to raise revenue from the colonies but to bail out the floundering East India Company, a key partner in the British economy. The British government granted the company a monopoly on the importation and sale of tea in the colonies. The colonists had never accepted the constitutionality of the duty on tea, and the Tea Act rekindled their opposition to it. Colonial resistance culminated in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, in which Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty boarded three East India Tea Company ships in the Boston harbor and threw 342 chests of tea overboard. The value of the tea was 10,000 Pounds Sterling (approximately $400,000 in U.S. Dollars today).

Hands-On Opportunity

We think of tea as dried leaves, or paper bags of dried leaves that are soaked in hot water to make the drink, tea. However, that is not what tea looked like in the 1700’s. To ship anything from as far away as India was expensive, even without considerations for the tax. Therefore, tea leaves were pressed into bricks. Reproduction bricks of tea are commercially available from reenacting suppliers such as Jas-Townsend and Sons. The bricks could be tightly packed into crates saving space. To make tea, a piece of compressed tea would be broken off and placed in a pot of boiling water. The tea bricks can be easily passed around a classroom.

Hands -On Learning Opportunity

Tea was the drink for the times. Things like coffee and soda were not available in the colonies. To enjoy a hot drink on a cold day, colonists would drink tea. What we consistently see in taxation is the selection of things that people use, like and are popular. Taxes can be used to punish or to raise money for a government by taxing popular items. Taxes on unpopular items are not a very practical thing. Consider a discussion on the popular items taxed in our society today.

The Quebec Act – 1774

The passing by the British Parliament of the Quebec Act in 1774 led to further anger in the Colonies. The Act guaranteed religious freedom for Roman Catholics and restored French civil law in the conquered colony of Québec – raising the ire of anti-Catholic American Protestants who resided in the colonies. The act:

- Expanded the Canadian province territory to take over part of the Indian Reserve, including much of what is now southern Ontario, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota.

- Reference to the Protestant faith was removed from the oath of allegiance.

- It guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic faith.

- It restored the use of the French civil law for matters of private law, except that in accordance with the English common law.

- It restored the Catholic Church’s right to impose tithes.

Religion, and the right to practice as you wish was a long-standing issue within Great Britain. Their insistence upon the King’s variant of the Anglican Church and the head of the church as the Archbishop of Canterbury was responsible for driving out many of the early settlers in the colonies. The Quebec Act would later manifest itself into what we all know today as the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights.

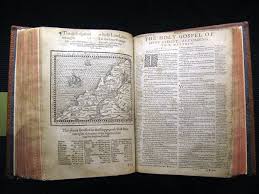

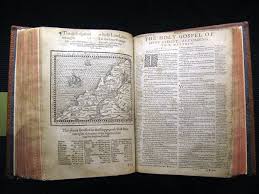

Hands-On Opportunity

Depending upon your venue and comfort zone, this is an excellent place to introduce the Bible as used by both Patriots and Loyalists. The Patriot Bible was the “Geneva Bible of 1599.” This was the first version of a Bible translated into English from the original Greek and Hebrew sacred scripts. This version of the Bible is significant because, for the very first time, a mechanically printed, mass-produced Bible was made available directly to the general public which came with a variety of scriptural study guides and aids, which included verse citations that allow the reader to cross-reference one verse with numerous relevant verses in the rest of the Bible, introductions to each book of the Bible that acted to summarize all of the material that each book would cover, maps, tables, woodcut illustrations and indices.

The Loyalists Bible could be called the King James Bible of 1611. King James I did not like the Geneva Bible. He thought that the many study guides, references and citations were confusing. James set out to create a Bible, true to its roots, translated directly from original scripts but with a very differing objective. Most of the people in these times could not read and their access to a Bible was through church where the verses were read aloud. When translators were assembled to do the work, there was a subtle directive to create a translation that would create visions of its meanings when heard. It is often interesting to show the difference between the two Bibles. There was a long and contentious history of abuses perpetrated by governments over specific religious beliefs. Two differing Bibles is just one example.

Learning Opportunity

Pages from the Geneva Bible

If you can find reprinted Bibles of the period, you can review the use of letters, spelling and other changes in the early English language. As time progresses, language and the meaning of words progress too. This is most important as each generation attempts to communicate with each other. While we may use the same words, the meanings may not be the same to each person. Hence, the “Generation Gap” exists.

Colonial Grievances Summary

This would be a very good point to summarize the major complaints building in the minds of the colonists just prior to the Revolution.

- The colonies were required to pay for a war that they were not permitted to fight for themselves. Part of payment was to also help Britain pay for the Seven Years War, something that did not even involve the colonies

- Colonial citizens could not stand up their own army.

- Colonies could not govern themselves by creating local groups of representatives.

- Colonial citizens could not peaceably complain about their taxes and lack of representation.

- Their governors and judges were not colonials, they were sent from Britain to rule over them.

- When tried for a crime, a colonist could not have other colonists as their jury.

- When colonies produced products for exports, they were required to sell them through a single source, the East India Tea Company and solely for the benefit of England prices that the East India Tea Company set.

- When they purchased products, they could not pick the lowest cost producer. Again, they had to purchase everything they imported from the East India Tea Company, usually at a higher price.

- They could not practice their own forms of religion, they had to belong to the Anglican Church of England.

- British troops were “quartering.” Taking their homes and supplies for themselves without fair compensation.

- The colonies had no say so over what was taxed or how high the tax should be.

- If caught attempting to purchase commodities from sources other than the East India Tea Company, their ships and cargo were seized. This happened to John Hancock and was the principle reason he entered the Revolution.

- Even the purchasing power, the value of currencies used by the colonies was under the control of the British Government.

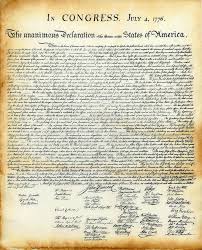

Learning Opportunity

At this point in your camp, present to them a list of historical events in chronological order. Discuss how this escalating list of actions against the rights of the colonists would have provoked them to action. You can compare this list with the actual grievances listed in the Declaration.